Psilocybin mushroom

Psilocybin mushrooms, or psilocybin-containing mushrooms, commonly known as magic mushrooms or as shrooms, are a type of hallucinogenic mushroom and a polyphyletic informal group of fungi that contain the psilocybin, which turns into the psychedelic psilocin upon ingestion.[1] The most potent species are members of genus Psilocybe, such as P. azurescens, P. semilanceata, and P. cyanescens, but psilocybin has also been isolated from approximately a dozen other genera, including Panaeolus (including Copelandia), Inocybe, Pluteus, Gymnopilus, and Pholiotina.[1]

Amongst other cultural applications, psilocybin mushrooms are used as recreational drugs.[1] They may be depicted in Stone Age rock art in Africa and Europe, but are more certainly represented in pre-Columbian sculptures and glyphs seen throughout the Americas.

History

[edit]Psilocybin mushrooms have been[when?] and continue to be used in Mexican and Central American cultures in religious, divinatory, or spiritual contexts.[2]

Early

[edit]

Rock art from c. 9000–7000 BCE from Tassili, Algeria, is believed to depict psychedelic mushrooms and the transformation of the user under their influence.[3] Prehistoric rock art near Villar del Humo in Spain suggests that Psilocybe hispanica was used in religious rituals 6,000 years ago.[4] The hallucinogenic[5] species of the Psilocybe genus have a history of use among the native peoples of Mesoamerica for religious communion, divination, and healing, from pre-Columbian times to the present day.[6] Mushroom stones and motifs have been found in Guatemala.[7] A statuette dating from c. 200 CE depicting a mushroom strongly resembling Psilocybe mexicana was found in the west Mexican state of Colima in a shaft and chamber tomb. A Psilocybe species known to the Aztecs as teōnanācatl (literally "divine mushroom": the agglutinative form of teōtl (god, sacred) and nanācatl (mushroom) in Nahuatl language) was reportedly served at the coronation of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II in 1502. Aztecs and Mazatecs referred to psilocybin mushrooms as genius mushrooms, divinatory mushrooms, and wondrous mushrooms when translated into English.[8] Bernardino de Sahagún reported the ritualistic use of teonanácatl by the Aztecs when he traveled to Central America after the expedition of Hernán Cortés.[9]

After the Spanish conquest, Catholic missionaries campaigned against the cultural tradition of the Aztecs, dismissing the Aztecs as idolaters, and the use of hallucinogenic plants and mushrooms, together with other pre-Christian traditions, was quickly suppressed.[7] The Spanish believed the mushroom allowed the Aztecs and others to communicate with demons. Despite this history, the use of teonanácatl has persisted in some remote areas.[2]

Modern

[edit]

The first mention of hallucinogenic mushrooms in European medicinal literature was in the London Medical and Physical Journal in 1799: A man served Psilocybe semilanceata mushrooms he had picked for breakfast in London's Green Park to his family. The apothecary who treated them later described how the youngest child "was attacked with fits of immoderate laughter, nor could the threats of his father or mother refrain him."[10]

In 1955, Valentina Pavlovna Wasson and R. Gordon Wasson became the first known European Americans to actively participate in an indigenous mushroom ceremony. The Wassons did much to publicize their experience, even publishing an article on their experiences in Life on May 13, 1957.[11] In 1956, Roger Heim identified the psychoactive mushroom the Wassons brought back from Mexico as Psilocybe,[12] and in 1958, Albert Hofmann first identified psilocybin and psilocin as the active compounds in these mushrooms.[13][14]

Inspired by the Wassons' Life article, Timothy Leary traveled to Mexico to experience psilocybin mushrooms himself. When he returned to Harvard in 1960, he and Richard Alpert started the Harvard Psilocybin Project, promoting psychological and religious studies of psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs. Alpert and Leary sought to conduct research with psilocybin on prisoners in the 1960s, testing its effects on recidivism.[15] This experiment reviewed the subjects six months later, and found that the recidivism rate had decreased beyond their expectation, below 40%. This, and another experiment administering psilocybin to graduate divinity students, showed controversy. Shortly after Leary and Alpert were dismissed from their jobs by Harvard in 1963, they turned their attention toward promoting the psychedelic experience to the nascent hippie counterculture.[16]

The popularization of entheogens by the Wassons, Leary, Terence McKenna, Robert Anton Wilson, and many others led to an explosion in the use of psilocybin mushrooms throughout the world. By the early 1970s, many psilocybin mushroom species were described from temperate North America, Europe, and Asia and were widely collected. Books describing methods of cultivating large quantities of Psilocybe cubensis were also published. The availability of psilocybin mushrooms from wild and cultivated sources has made them one of the most widely used psychedelic drugs.

At present, psilocybin mushroom use has been reported among some groups spanning from central Mexico to Oaxaca, including groups of Nahua, Mixtecs, Mixe, Mazatecs, Zapotecs, and others.[2] An important figure of mushroom usage in Mexico was María Sabina,[17] who used native mushrooms, such as Psilocybe mexicana in her practice.

Occurrence

[edit]In a 2000 review on the worldwide distribution of psilocybin mushrooms, Gastón Guzmán and colleagues considered these distributed among the following genera: Psilocybe (116 species), Gymnopilus (14), Panaeolus (13), Copelandia (12), Pluteus (6) Inocybe (6), Pholiotina (4) and Galerina (1).[18][19] Guzmán increased his estimate of the number of psilocybin-containing Psilocybe to 144 species in a 2005 review.

Many of them are found in Mexico (53 species), with the remainder distributed throughout Canada and the US (22), Europe (16), Asia (15), Africa (4), and Australia and associated islands (19).[21] Generally, psilocybin-containing species are dark-spored, gilled mushrooms that grow in meadows and woods in the subtropics and tropics, usually in soils rich in humus and plant debris.[22] Psilocybin mushrooms occur on all continents, but the majority of species are found in subtropical humid forests.[18] P. cubensis is the most common Psilocybe in tropical areas. P. semilanceata, considered the world's most widely distributed psilocybin mushroom,[23] is found in temperate parts of Europe, North America, Asia, South America, Australia and New Zealand, although it is absent from Mexico.[21]

Some bolete mushrooms, which are not closely related to any known psilocybin-containing mushroom species, have been reported to be hallucinogenic mushrooms, for instance in the Yunnan province in China.[24][25] The exact species as well specific active compounds in these mushrooms are not known, although unidentified indolic compounds were detected by Albert Hofmann in some boletes such as Boletus manicus.[25]

Composition

[edit]| Phosphorylated | Dephosphorylated | HTR? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norbaeocystin (4-PT) | 4-Hydroxytryptamine (4-HT) | No | ||||

| Baeocystin (4-PO-NMT) | Norpsilocin (4-HO-NMT) | No | ||||

| Psilocybin (4-PO-DMT) | Psilocin (4-HO-DMT) | Yes | ||||

| Aeruginascin (4-PO-TMT) | 4-HO-TMT | No | ||||

| Notes: (1) The phosphorylated constituents are or are thought to be prodrugs of the dephosphorylated constituents. (2) The head-twitch response (HTR) is a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects in rodents. Refs: [1][26][27][28] | ||||||

Magic mushroom composition varies from genus to genus and species to species.[29] Its principal component is psilocybin,[30] which is converted into psilocin to produce psychoactive effects.[31][32] Besides psilocin, norpsilocin, baeocystin, norbaeocystin, and aeruginascin may also be present, which might result in an entourage effect and modify the effects of magic mushrooms.[1][29] Animal studies suggest that the effects of pure psilocybin or psilocin and psilocybin mushrooms may be different and support the possibility of such an entourage effect with psilocybin mushrooms.[1][33][34] Panaeolus subbalteatus, one species of magic mushroom, had the highest amount of psilocybin compared to the rest of the fruiting body.[29]

Certain mushrooms are found to produce β-carbolines, such as harmine, harmane, tetrahydroharmine (THH), and harmaline, which inhibit monoamine oxidase (MAO), an enzyme that breaks down tryptamine alkaloids, and have other actions.[35][1] They occur in different genera, such as Psilocybe,[35][36] Cyclocybe,[37] and Hygrophorus.[38] Harmine, harmane, norharmane, and a range of other β-carbolines were discovered in Psilocybe species.[35] β-Carbolines in psilocybin mushrooms may inhibit the metabolism of psilocybin and other constituents and thereby potentiate their effects.[35]

Effects

[edit]

The effects of psilocybin mushrooms come from psilocybin and psilocin. When psilocybin is ingested, it is broken down by the liver in a process called dephosphorylation. The resulting compound is called psilocin, responsible for the psychedelic effects.[40] Psilocybin and psilocin create short-term increases in tolerance of users, thus making it difficult to misuse them because the more often they are taken within a short period, the weaker the resultant effects are.[41] Psilocybin mushrooms have not been known to cause physical or psychological dependence (addiction).[42] The psychedelic effects appear around 20 minutes after ingestion and can last up to 6 hours. Physical effects may occur, including nausea, vomiting, euphoria, muscle weakness or relaxation, drowsiness, and lack of coordination.

As with many psychedelic substances, the effects of psychedelic mushrooms are subjective and can vary considerably among individual users. The mind-altering effects of psilocybin-containing mushrooms typically last from three to eight hours, depending on dosage, preparation method, and personal metabolism. The first 3–4 hours after ingestion are typically referred to as the 'peak'—in which the user experiences more vivid visuals and distortions in reality. The effects can seem to last much longer for the user because of psilocybin's ability to alter time perception.[43]

Sensory

[edit]Sensory effects include visual and auditory hallucinations followed by emotional changes and altered perception of time and space.[44] Noticeable changes to the auditory, visual, and tactile senses may become apparent around 30 minutes to an hour after ingestion, although effects may take up to two hours to take place. These shifts in perception visually include enhancement and contrasting of colors, strange light phenomena (such as auras or "halos" around light sources), increased visual acuity, surfaces that seem to ripple, shimmer, or breathe; complex open and closed eye visuals of form constants or images, objects that warp, morph, or change solid colors; a sense of melting into the environment, and trails behind moving objects. Sounds may seem to have increased clarity—music, for example, can take on a profound sense of cadence and depth.[44] Some users experience synesthesia, wherein they perceive, for example, a visualization of color upon hearing a particular sound.[45]

Emotional

[edit]As with other psychedelics such as LSD, the experience, or 'trip,' is strongly dependent upon set and setting.[44] Hilarity, lack of concentration, and muscular relaxation (including dilated pupils) are all normal effects, sometimes in the same trip.[44] A negative environment could contribute to a bad trip, whereas a comfortable and familiar environment would set the stage for a pleasant experience. Psychedelics make experiences more intense, so if a person enters a trip in an anxious state of mind, they will likely experience heightened anxiety on their trip. Many users find it preferable to ingest the mushrooms with friends or people familiar with 'tripping.'[46] The psychological consequences of psilocybin use include hallucinations and an inability to discern fantasy from reality. Panic reactions and psychosis also may occur, particularly if a user ingests a large dose.[47]

Dosage

[edit]

The dosage of psilocybin-containing mushrooms depends on the psilocybin and psilocin content, which can vary significantly between and within the same species.[48][1][49] Psilocybin content is typically around 0.5% to 1% of the dried weight of the mushroom, with a range of 0.03% to 1.78%.[1][50][51][52][53] Psilocin is also often present in the mushrooms, with a range of 0% to 0.59%, and can be on par with or an order of magnitude lower than psilocybin levels.[50][1] Psilocybe cubensis, the most popular species, has been reported to contain 0.63% psilocybin and 0.6% psilocin, or about 1.2% of psilocybin and psilocin combined.[50] However, there is significant variation in different P. cubensis strains.[54][55] The 'Penis Envy' strain of P. cubensis is considered to be more potent than other strains.[54] Psilocybin levels appear to be highest in P. cyanescens and/or P. azurescens.[1][50][56]

Recreational doses of psilocybin mushrooms are typically between 1.0 to 3.5–5.0 g of dry mushrooms and 10 to 50 g of fresh mushrooms.[48][51] This corresponds to a dosage of psilocybin of about 10 to 50 mg.[51] Usual doses of the common species P. cubensis range around 1.0 to 2.5 g, while about 2.5 to 5.0 g dried mushroom material is considered a strong dose and above 5.0 g is considered a heavy dose.[57] A 5.0 g dose of dried mushroom is often referred to as a "heroic dose".[58] In terms of psilocybin dosing, subthreshold or microdoses are <2.5 mg, low doses are 5 to 10 mg, the intermediate or "good effect" dose is 20 mg, and high or ego-dissolution doses are 30 to 40 mg.[59][48] A 20 mg dose of psilocybin is equivalent to about 100 μg LSD or about 500 mg mescaline.[59] With regard to psilocybin and psilocin equivalence, psilocin is about 1.4-fold more potent than psilocybin (i.e., 1.4 mg psilocybin equals about 1.0 mg psilocin).[50][60]

Microdosing has become a popular technique for many users, which involves taking <1.0 g of dried mushrooms for an experience that is not as intense or powerful, but recreationally enjoyable, or fully non-hallucinogenic, and potentially alleviating for symptoms of depression.[61] A microdose of psilocybin mushrooms is about 10% of a recreational dose, and may be 0.1 to 0.3 g of dry mushrooms, taken up to three times per week.[62]

Toxicology

[edit]The species within the most commonly foraged and ingested genus of psilocybin mushrooms, the psilocybe, contains two primary hallucinogenic toxins; psilocybin and psilocin.[63] The median lethal dose, also known as "LD50", of psilocybin is 280 mg/kg.[64]

From a toxicological profile, it would be incredibly difficult to overdose on psilocybin mushrooms, given their primary toxin compounds. To consume such massive amounts of psilocybin, one must ingest more than 1.2 kg of dried Psilocybe cubensis given 1-2% of the dried mushroom contains psilocybin.[52]

Posing a more realistic threat than a lethal overdose, significantly elevated levels of psilocin can overstimulate the 5-HT2A receptors in the brain, causing acute serotonin syndrome.[65] A 2015 study observed that a dose of 200 mg/kg psilocin induced symptoms of acute serotonin poisoning in mice.[66]

Neurotoxicity-induced fatal events are uncommon with psilocybin mushroom overdose, as most patients admitted to critical care are released from the department only requiring moderate treatment.[65] However, fatal events related to emotional distress and trip-induced psychosis can occur as a result of over-consumption of psilocybin mushrooms. In 2003, a 27-year-old man was found dead in an irrigation canal due to hypothermia. In his bedroom was found two cultivation pots of psilocybin mushrooms, but no report of toxicology was made.[67]

Clinical research

[edit]Due partly to restrictions of the Controlled Substances Act, research in the United States was limited until the early 21st century when psilocybin mushrooms were tested for their potential to treat drug dependence, anxiety and mood disorders.[68][69] In 2018–19, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation for studies of psilocybin in depressive disorders.[70]

Legality

[edit]The legality of the cultivation, possession, and sale of psilocybin mushrooms and psilocybin and psilocin varies from country to country.

After Oregon Measure 109, in 2020, Oregon became the first US state to decriminalize psilocybin and legalize it for therapeutic use. However, selling psilocybin without being licensed may still attract fines or imprisonment.[71] In 2022 Colorado legalized consumption, growing, and sharing for personal use,[72] though sales are prohibited while regulations are being drafted.[73][74] Other jurisdictions in the United States where psilocybin mushrooms are decriminalized include Ann Arbor and Detroit, Michigan; Oakland and Santa Cruz, California; Easthampton, Somerville, Northampton, and Cambridge, Massachusetts; Seattle, Washington; and Washington, DC.

Furthermore, buying spores of mushroom species containing psilocybin online in the United States is legal in all states except Georgia, Idaho and California.[75] This is because only fruiting mushrooms and mycelium contain psilocybin, a federally banned substance.[76] A technical caveat to consider, however, is that the distributed spores must not be intended to be used for cultivation, but allowed for microscopy purposes.[77]

United Nations

[edit]

Internationally, mescaline, DMT, and psilocin, are Schedule I drugs under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The Commentary on the Convention on Psychotropic Substances notes, however, that the plants containing them are not subject to international control:[78]

The cultivation of plants from which psychotropic substances are obtained is not controlled by the Vienna Convention... Neither the crown (fruit, mescal button) of the Peyote cactus nor the roots of the plant Mimosa hostilis nor Psilocybe mushrooms themselves are included in Schedule 1, but only their respective principals, mescaline, DMT, and psilocin.

See also

[edit]- Psilocybin

- List of psilocybin mushroom species

- List of psychoactive plants, fungi, and animals

- List of psychoactive substances derived from artificial fungi biotransformation

- Mushroom edible

- Mushroom tea

- Psilocybin decriminalization in the United States

- Psychedelic mushroom store

- Stoned ape theory

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pepe M, Hesami M, de la Cerda KA, Perreault ML, Hsiang T, Jones AM (December 2023). "A journey with psychedelic mushrooms: From historical relevance to biology, cultivation, medicinal uses, biotechnology, and beyond". Biotechnol Adv. 69: 108247. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108247. PMID 37659744.

On a dry weight basis, psilocybin content within the basidiocarp ranges from 0.03% to 1.6% across various Psilocybe species (Anastos et al., 2006; Beug and Bigwood, 1982; Fricke et al., 2019; Gartz et al., 1994; Pedersen-Bjergaard et al., 1997). However, newly developed lineages with higher average amounts of psilocybin are continuously being produced. A recent survey of 14 Psilocybe species sourced from around the world established that tryptamine content including psilocybin is greatest in P. cyanescens, whereas Psilocybe fus cofulva contains no psilocybin (Gotvaldova ´ et al., 2022). Tryptamines can also vary across varieties of a species, and their individual collec tions as is the case for Psilocybe serbica varieties 'arcana', bohemica' and 'moravica' (Boroviˇcka et al., 2015; Gotvaldova ´ et al., 2022; Reynolds et al., 2018). Psilocybin levels can be on par to an order of magnitude greater than psilocin levels (Borner and Brenneisen, 1987; Gartz et al., 1994; Gotvaldov´ a et al., 2022). [...] With respect to other tryptamines, baeocystin content is absent in some psilocybin-containing species but as high as 0.45% on a dry weight basis in certain species (Christiansen and Rasmussen, 1982; Gartz et al., 1994; Gotvaldova ´ et al., 2022; Pedersen-Bjergaard et al., 1997). [...] Apart from the abovementioned tryptamines, β-carbolines such as harmane and har mine are also known to occur in Psilocybe, albeit at 0.1% or less of psilocybin levels in these same mushrooms (Blei et al., 2020). [...] Additionally, various compounds can collectively contribute to what is known as "the entourage effect", which describes the synergistic interaction of a variety of different metabolites that enhance the activity of the primary active components (Russo, 2019). Tryptamine concentrations and profiles across different Psilocybe species are highly variable. Thus, the diversity of Psilocybe species results in differential production of an assortment of tryptamines in different concentrations (Glatfelter et al., 2022), which is likely responsible for variable psychoactive effects of various mushrooms.

- ^ a b c Guzmán G. (2008). "Hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico: An overview". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 404–412. Bibcode:2008EcBot..62..404G. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9033-8. S2CID 22085876.

- ^ Samorini, Giorgio (1992). "The oldest representations of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the world (Sahara Desert, 9000-7000 BP)". Integration. Zeitschrift für geistbewegende Pflanzen und Kultur. 2/3: 69–75.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Akers, Brian P.; Ruiz, Juan Francisco; Piper, Alan; Ruck, Carl A. P. (2011). "A Prehistoric Mural in Spain Depicting Neurotropic Psilocybe Mushrooms?1". Economic Botany. 65 (2): 121–128. doi:10.1007/s12231-011-9152-5. S2CID 3955222.

- ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (April 22, 2019). "Hallucinogens DrugFacts". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ F.J. Carod-Artal (January 1, 2015). "Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures". Neurología (English Edition). 30 (1): 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010. PMID 21893367.

- ^ a b Stamets (1996), p. 11.

- ^ Stamets (1996), p. 7.

- ^ Hofmann A. (1980). "The Mexican relatives of LSD". LSD: My Problem Child. New York City: McGraw-Hill. pp. 49–71. ISBN 978-0-07-029325-0.

- ^ Brande E. (1799). "Mr. E. Brande, on a poisonous species of Agaric". The Medical and Physical Journal: Containing the Earliest Information on Subjects of Medicine, Surgery, Pharmacy, Chemistry, and Natural History. 3 (11): 41–44. PMC 5659401. PMID 30490162. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ Wasson RG (1957). "Seeking the magic mushroom". Life. No. May 13. pp. 100–120. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ Heim R. (1957). "Notes préliminaires sur les agarics hallucinogènes du Mexique" [Preliminary notes on the hallucination-producing agarics of Mexico]. Revue de Mycologie (in French). 22 (1): 58–79.

- ^ Hofmann A, Frey A, Ott H, Petrzilka T, Troxler F (1958). "Konstitutionsaufklärung und Synthese von Psilocybin" [The composition and synthesis of psilocybin]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (in German). 14 (11): 397–399. doi:10.1007/BF02160424. PMID 13609599. S2CID 33692940.

- ^ Hofmann A, Heim R, Brack A, Kobel H (1958). "Psilocybin, ein psychotroper Wirkstoff aus dem mexikanischen Rauschpilz Psilocybe mexicana Heim" [Psilocybin, a psychotropic drug from the Mexican magic mushroom Psilocybe mexicana Heim]. Experientia (in German). 14 (3): 107–109. doi:10.1007/BF02159243. PMID 13537892. S2CID 42898430.

- ^ "Dr. Leary's Concord Prison Experiment: A 34-Year Follow-Up Study". Bulletin of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 9 (4): 10–18. 1999. Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Lattin, Don (2010). The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil killed the fifties and ushered in a new age for America (1st ed.). New York: HarperOne. pp. 37–44. ISBN 978-0-06-165593-7.

- ^ Monaghan, John D.; Cohen, Jeffrey H. (2000). "Thirty years of Oaxacan ethnography". In Monaghan, John; Edmonson, Barbara (eds.). Ethnology. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-292-70881-5.

- ^ a b Guzmán, G.; Allen, J.W.; Gartz, J. (2000). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion" (PDF). Annali del Museo Civico di Rovereto: Sezione Archeologia, Storia, Scienze Naturali. 14: 189–280. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ Gotvaldova, Klara; Borovicka, Jan; Hajkova, Katerina; Cihlarova, Petra; Rockefeller, Alan; Kuchar, Martin (2022). "Extensive Collection of Psychotropic Mushrooms with Determination of Their Tryptamine Alkaloids". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (22): 14068. doi:10.3390/ijms232214068. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 9693126. PMID 36430546.

- ^ Guzmán G, Allen JW, Gartz J (1998). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion" (PDF). Annali del Museo Civico di Rovereto. 14: 207. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Guzmán, G. (2005). "Species diversity of the genus Psilocybe (Basidiomycotina, Agaricales, Strophariaceae) in the world mycobiota, with special attention to hallucinogenic properties". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 7 (1–2): 305–331. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v7.i12.280.

- ^ Wurst, M.; Kysilka, R.; Flieger, M. (2002). "Psychoactive tryptamines from Basidiomycetes". Folia Microbiologica. 47 (1): 3–27 [5]. doi:10.1007/BF02818560. PMID 11980266. S2CID 31056807.

- ^ Guzmán, G. (1983). The Genus Psilocybe: A Systematic Revision of the Known Species Including the History, Distribution, and Chemistry of the Hallucinogenic Species. Beihefte Zur Nova Hedwigia. Vol. 74. Vaduz, Liechtenstein: J. Cramer. pp. 361–2. ISBN 978-3-7682-5474-8.

- ^ Guzmán G (2015). "New Studies on Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: History, Diversity, and Applications in Psychiatry". Int J Med Mushrooms. 17 (11): 1019–1029. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushrooms.v17.i11.10. PMID 26853956.

- ^ a b Arora, David (2008). "Notes on Economic Mushrooms. Xiao Ren Ren: The "Little People" of Yunnan" (PDF). Economic Botany. 62 (3). New York Botanical Garden Press: 540–544. ISSN 0013-0001. JSTOR 40390492. Retrieved February 18, 2025.

- ^ Sherwood AM, Halberstadt AL, Klein AK, McCorvy JD, Kaylo KW, Kargbo RB, Meisenheimer P (February 2020). "Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Tryptamines Found in Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Norbaeocystin, Baeocystin, Norpsilocin, and Aeruginascin". J Nat Prod. 83 (2): 461–467. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01061. PMID 32077284.

- ^ Glatfelter GC, Pottie E, Partilla JS, Sherwood AM, Kaylo K, Pham DN, Naeem M, Sammeta VR, DeBoer S, Golen JA, Hulley EB, Stove CP, Chadeayne AR, Manke DR, Baumann MH (November 2022). "Structure-Activity Relationships for Psilocybin, Baeocystin, Aeruginascin, and Related Analogues to Produce Pharmacological Effects in Mice". ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 5 (11): 1181–1196. doi:10.1021/acsptsci.2c00177. PMC 9667540. PMID 36407948.

- ^ Rakoczy RJ, Runge GN, Sen AK, Sandoval O, Wells HG, Nguyen Q, Roberts BR, Sciortino JH, Gibbons WJ, Friedberg LM, Jones JA, McMurray MS (October 2024). "Pharmacological and behavioural effects of tryptamines present in psilocybin-containing mushrooms". Br J Pharmacol. 181 (19): 3627–3641. doi:10.1111/bph.16466. PMID 38825326.

- ^ a b c "Chemical Composition Variability in Magic Mushrooms". Psychedelic Science Review. March 4, 2019. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Hallucinogenic mushrooms drug profile". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ Kuhn, Cynthia; Swartzwelder, Scott; Wilson, Wilkie (2003). Buzzed: The Straight Facts about the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-393-32493-8.

- ^ Canada, Health (January 12, 2012). "Magic mushrooms – Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Lerer L, Botvinnik A, Spear K, Shahar O, Lipski P, Calderon H, Blakolmer K, Lifschytz T, Lerer B (December 2022). "ACNP 61st Annual Meeting: Poster Abstracts P271-P540: P425. Tripping Mice and Stoned Fish: Head Twitch Response (HTR) and Behavioral Phenotypic Evidence of Effect Differences Between Synthetic Psilocybin and Psychedelic Mushroom Extract". Neuropsychopharmacology. 47 (Suppl 1): 220–370 (308–309). doi:10.1038/s41386-022-01485-0. PMC 9714399. PMID 36456694.

- ^ Zhuk O, Jasicka-Misiak I, Poliwoda A, Kazakova A, Godovan VV, Halama M, Wieczorek PP (March 2015). "Research on acute toxicity and the behavioral effects of methanolic extract from psilocybin mushrooms and psilocin in mice". Toxins (Basel). 7 (4): 1018–1029. doi:10.3390/toxins7041018. PMC 4417952. PMID 25826052.

- ^ a b c d Plazas E, Faraone N (February 2023). "Indole Alkaloids from Psychoactive Mushrooms: Chemical and Pharmacological Potential as Psychotherapeutic Agents". Biomedicines. 11 (2): 461. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11020461. PMC 9953455. PMID 36830997.

- ^ Blei F, Dörner S, Fricke J, Baldeweg F, Trottmann F, Komor A, Meyer F, Hertweck C, Hoffmeister D (January 2020). "Simultaneous Production of Psilocybin and a Cocktail of β-Carboline Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors in 'Magic' Mushrooms". Chemistry: A European Journal. 26 (3): 729–734. doi:10.1002/chem.201904363. PMC 7003923. PMID 31729089.

- ^ Krüzselyi D, Vetter J, Ott PG, Darcsi A, Béni S, Gömöry Á, Drahos L, Zsila F, Móricz ÁM (September 2019). "Isolation and structural elucidation of a novel brunnein-type antioxidant β-carboline alkaloid from Cyclocybe cylindracea". Fitoterapia. 137: 104180. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2019.104180. PMID 31150766. S2CID 172137046.

- ^ Teichert A, Lübken T, Schmidt J, Kuhnt C, Huth M, Porzel A, Wessjohann L, Arnold N (2008). "Determination of beta-carboline alkaloids in fruiting bodies of Hygrophorus spp. by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry". Phytochemical Analysis. 19 (4): 335–41. Bibcode:2008PChAn..19..335T. doi:10.1002/pca.1057. PMID 18401852.

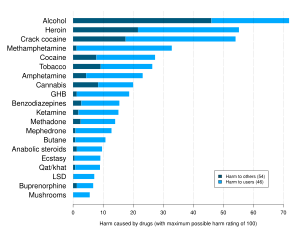

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Passie, T.; Seifert, J.; Schneider, und; Emrich, H.M. (2002). "The pharmacology of psilocybin". Addiction Biology. 7 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1080/1355621021000005937. PMID 14578010. S2CID 12656091.

- ^ "Psilocybin Fast Facts". National Drug Intelligence Center. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ van Amsterdam, J.; Opperhuizen, A.; van den Brink, W. (2011). "Harm potential of magic mushroom use: A review". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 59 (3): 423–429. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006. PMID 21256914.

- ^ Wittmann, M.; Carter, O.; Hasler, F.; Cahn, B.R.; Grimberg, und; Spring, P.; Hell, D.; Flohr, H.; Vollenweider, F.X. (2007). "Effects of psilocybin on time perception and temporal control of behavior in humans". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 21 (1): 50–64. doi:10.1177/0269881106065859. PMID 16714323. S2CID 3165579.

- ^ a b c d Schultes, Richard Evans (1976). Hallucinogenic Plants. Illustrated by Elmer W. Smith. New York: Golden Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-307-24362-1.

- ^ Ballesteros, S.; Ramón, M.F.; Iturralde, M.J.; Martínez-Arrieta, R. (2006). "Natural Sources of Drugs of Abuse: Magic Mushrooms". In Cole, S.M. (ed.). New Research on Street Drugs. Nova Science Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-59454-961-8. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ Stamets (1996)

- ^ "Psilocybin Fast Facts". National Drug Intelligence Center, US Department of Justice. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c van Amsterdam J, Opperhuizen A, van den Brink W (April 2011). "Harm potential of magic mushroom use: a review" (PDF). Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 59 (3): 423–429. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006. PMID 21256914.

Magic mushrooms show a large variation in potency; their potency depends on the species or variety that is used, their origin, growing conditions and age. P. cubensis and Psilocybe semilanceata or 'Psilocybe', commonly known as liberty caps, contain 10 mg of psylocybin per gram of dried mushroom weight (1% w/w). Some other species (e.g. Psilocybe azurenscens and Psilocybe bohemica) contain slightly more psylocybin. The averaged dose of psilocybin that induces hallucinogenic effects is 4–10 mg (Beck et al., 1998) or 50–300 μg/kg body weight (Hasler et al., 2004), and therefore the minimum amount of mushrooms needed to get the desired recreational effect is about 1 g of dried magic mushrooms or 10 g of fresh magic mushrooms. The dose 'recommended' for recreational use is reported to be somewhat higher: between 1 and 3.5–5 g of dried mushrooms or 10–50 g for fresh mushrooms (Erowid, 2006). These dose ranges should be interpreted with caution, because it is difficult to estimate the dose of the active or hallucinogenic substance (e.g. psilocybin) into mushrooms (weight or number), as the concentration may vary. Furthermore, in addition to psilocybin and psilocin usually other pharmacologically active substance like indoles, phenylethylamines and baeocystin are present in magic mushrooms. However, as short-term tolerance may develop rapidly to both physical and psychological effect, dosages may have to be increased to obtain the desired effect.

- ^ Bigwood J, Beug MW (1982). "Variation of psilocybin and psilocin levels with repeated flushes (harvests) of mature sporocarps of Psilocybe cubensis (Earle) Singer". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 5 (3): 287–291. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(82)90014-9. PMID 7201054.

- ^ a b c d e Tylš F, Páleníček T, Horáček J (March 2014). "Psilocybin--summary of knowledge and new perspectives" (PDF). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 24 (3): 342–356. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. PMID 24444771.

The content of psilocybin and psilocin in hallucinogenic mushrooms varies in the range from 0.2% to 1% of dry weight (Table 2.). [...] Table 2 Content of psilocybin and psilocin in the dry state of selected representatives of psychoactive mushrooms, x=content is not known. [...] An equimolar dose to 1 mol of psilocin is 1.4 mol of psilocybin (Wolbach et al., 1962).

- ^ a b c Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, Valentine H, Grant J, Ali A, Ngwa W, Gordon L (May 2021). "The Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin" (PDF). Molecules. 26 (10). doi:10.3390/molecules26102948. PMC 8156539. PMID 34063505.

Even though there is interest in the extraction of psilocybin from naturally growing or cultivated mushrooms, the psilocybin yield obtained (0.1–0.2% of dry weight) is not economically viable for drug research and development [...] Recreationally, users typically ingest anywhere between 10–50 g of fresh mushrooms (1–5 g of dried mushrooms), which corresponds to a dosage of about 10–50 mg psilocybin [233].

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Laussmann, Tim; Meier-Giebing, Sigrid (2010). "Forensic analysis of hallucinogenic mushrooms and khat (Catha edulisForsk) using cation-exchange liquid chromatography". Forensic Science International. 1 (3): 160–164. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.12.013. PMID 20047807.

- ^ Nichols DE (October 2020). "Psilocybin: from ancient magic to modern medicine" (PDF). J Antibiot (Tokyo). 73 (10): 679–686. doi:10.1038/s41429-020-0311-8. PMID 32398764.

Total psilocybin and psilocin levels in species known to be used recreationally varied from 0.1% to nearly 2% by dry weight [8]. The medium oral dose of psilocybin is 4–8 mg, which elicits the same symptoms as the consumption of about 2 g of dried Psilocybe Mexicana [9].

- ^ a b Kurzbaum, Eyal; Páleníček, Tomáš; Shrchaton, Amiel; Azerrad, Sara; Dekel, Yaron (January 28, 2025). "Exploring Psilocybe cubensis Strains: Cultivation Techniques, Psychoactive Compounds, Genetics and Research Gaps". Journal of Fungi. 11 (2): 99. doi:10.3390/jof11020099. ISSN 2309-608X.

Prior to detailing specific strains, it is important to acknowledge that the following examples are predominantly sourced from non-academic, community-based reports. This is due, in part, to legislative restrictions on psilocybin, which have limited formal academic research on Psilocybe species. The following descriptions provide a nuanced understanding of the variety within P. cubensis strains. Among the most prominent strains, 'Golden Teacher' is renowned for its vigorous growth and substantial psychotropic effects, garnering substantial preference among both novices and experienced mycologists. The 'B+' strain is lauded for its resilience and consistent productivity under diverse environmental conditions. Furthermore, the 'Penis Envy' strain is noted for its exceptional potency and distinct morphological characteristics, which have contributed to its recognition and prominence within the community.

- ^ Goff R, Smith M, Islam S, Sisley S, Ferguson J, Kuzdzal S, Badal S, Kumar AB, Sreenivasan U, Schug KA (February 2024). "Determination of psilocybin and psilocin content in multiple Psilocybe cubensis mushroom strains using liquid chromatography - tandem mass spectrometry". Anal Chim Acta. 1288: 342161. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2023.342161. PMID 38220293.

A method for clinical potency determination of psilocybin and psilocin in hallucinogenic mushroom species Psilocybe cubensis was developed using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Five strains of dried, intact mushrooms were obtained and analyzed: Blue Meanie, Creeper, B-Plus, Texas Yellow, and Thai Cubensis. [...] From most to least potent, the study found that the average total psilocybin and psilocin concentrations for the Creeper, Blue Meanie, B+, Texas Yellow, and Thai Cubensis strains were 1.36, 1.221, 1.134, 1.103, and 0.879 % (w/w), respectively.

- ^ Gotvaldová K, Borovička J, Hájková K, Cihlářová P, Rockefeller A, Kuchař M (November 2022). "Extensive Collection of Psychotropic Mushrooms with Determination of Their Tryptamine Alkaloids". Int J Mol Sci. 23 (22). doi:10.3390/ijms232214068. PMC 9693126. PMID 36430546.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Erowid (2006). "Erowid Psilocybin Mushroom Vault: Dosage" (shtml). Erowid. Archived from the original on December 23, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ "Terence McKenna's Last Trip". Wired Magazine. Condé Nast Publications. May 1, 2000. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Holze F, Singh N, Liechti ME, D'Souza DC (May 2024). "Serotonergic Psychedelics: A Comparative Review of Efficacy, Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Binding Profile". Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 9 (5): 472–489. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2024.01.007. PMID 38301886.

- ^ Wolbach AB, Miner EJ, Isbell H (1962). "Comparison of psilocin with psilocybin, mescaline and LSD-25". Psychopharmacologia. 3: 219–223. doi:10.1007/BF00412109. PMID 14007905.

Psilocin is approximately 1.4 times as potent as psilocybin. This ratio is the same as that of the molecular weights of the two drugs.

- ^ Dana G Smith (2022). "More People Are Microdosing for Mental Health. But Does It Work?" (shtml). The New York Times. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Kozlowska U, Nichols C, Wiatr K, Figiel M (July 2022). "From psychiatry to neurology: Psychedelics as prospective therapeutics for neurodegenerative disorders". J Neurochem. 162 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1111/jnc.15509. PMID 34519052.

One dosing method of psychedelics is the use of so called "microdoses"—very low concentrations of various psychedelics that do not reach the threshold of perceivable behavioral effects. This is usually 10% of active recreational doses (e.g., 10–15 µg of LSD, or 0.1–0.3 g of dry "magic mushrooms") taken up to three times per week.

- ^ Kosentka, Pawel (2013). "Evolution of the toxins muscarine and psilocybin in a family of mushroom-forming fungi". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e64646. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864646K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064646. PMC 3662758. PMID 23717644.

- ^ Maryadele, O'Neil (2006). The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. Merck Research Laboratories. ISBN 978-0911910001.

- ^ a b Chilton, Scott; Bigwood, Jeremy (1979). "Chilton, W. Scott, Jeremy Bigwood, and Robert E. Jensen. "Psilocin, bufotenine, and serotonin: historical and biosynthetic observations". Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. 11.1 (2): 61–69. doi:10.1080/02791072.1979.10472093. PMID 392119. Archived from the original on December 24, 2022. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ^ Zhuk, Olga (2015). "Research on acute toxicity and the behavioral effects of methanolic extract from psilocybin mushrooms and psilocin in mice". Toxins. 7 (4): 1018–1029. doi:10.3390/toxins7041018. PMC 4417952. PMID 25826052.

- ^ Lima, Afonso DL (2012). "Poisonous mushrooms; a review of the most common intoxications" (PDF). Nutricion Hospitalaria. 27 (2): 402–408. doi:10.3305/nh.2012.27.2.5328. PMID 22732961. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 24, 2022. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ^ Bui, Eric; King, Franklin; Melaragno, Andrew (December 1, 2019). "Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders in the 21st century: A call for novel approaches (Review)". General Psychiatry. 32 (6): e100136. doi:10.1136/gpsych-2019-100136. PMC 6936967. PMID 31922087.

- ^ Doblin, Richard E.; Christiansen, Merete; Jerome, Lisa; Burge, Brad (March 15, 2019). "The Past and Future of Psychedelic Science: An Introduction to This Issue". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 51 (2): 93–97. doi:10.1080/02791072.2019.1606472. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 31132970. S2CID 167220251.

- ^ "FDA grants Breakthrough Therapy Designation to Usona Institute's psilocybin program for major depressive disorder". Business Wire. November 22, 2019. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Oregon Measure 109, Psilocybin Mushroom Services Program Initiative (2020)". ballotpedia.org. November 3, 2020. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Jennifer (November 10, 2022). "Colorado becomes second state to legalize "magic mushrooms"". The Colorado Sun. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ "A gray market emerges in Colorado after voters approved psychedelic substances". NPR. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ "Colorado Proposition 122, Decriminalization and Regulated Access Program for Certain Psychedelic Plants and Fungi Initiative (2022)". ballotpedia.org. November 8, 2022. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". sporestock.com. July 2, 2022. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "Psilocybin Drug Fact Sheet" (PDF). dea.gov. April 21, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "COURT OF APPEALS OF WISCONSIN PUBLISHED OPINION" (PDF). wicourts.gov. June 21, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ DMT – UN report, MAPS, March 31, 2001, archived from the original on January 21, 2012, retrieved January 14, 2012

Further reading

[edit]- Allen, J.W. (1997). Magic Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Raver Books and John W. Allen. ISBN 978-1-58214-026-1.

- Estrada, A. (1981). Maria Sabina: Her Life and Chants. Ross Erikson. ISBN 978-0-915520-32-9.

- Haze, Virginia & Dr. K. Mandrake, PhD. The Psilocybin Mushroom Bible: The Definitive Guide to Growing and Using Magic Mushrooms. Green Candy Press: Toronto, Canada, 2016. ISBN 978-1-937866-28-0. www.greencandypress.com.

- Högberg, O. (2003). Flugsvampen och människan (in Swedish). Carlssons. ISBN 978-91-7203-555-3.

- Kuhn, C.; Swartzwelder, S; Wilson, W. (2003). Buzzed: The Straight Facts about the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32493-8.

- Letcher, A. (2006). Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22770-9.

- McKenna, T. (1993). Food of the Gods. Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-37130-7.

- Nicholas, L.G.; Ogame, K. (2006). Psilocybin Mushroom Handbook: Easy Indoor and Outdoor Cultivation. Quick American Archives. ISBN 978-0-932551-71-9.

- Stamets, P. (1993). Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-1-58008-175-7.

- Stamets, P.; Chilton, J.S. (1983). The Mushroom Cultivator. Olympia: Agarikon Press. ISBN 978-0-9610798-0-2.

- Stamets, P. (1996). Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 9780898158397.

- Wasson, G.R. (1980). The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-068443-0.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of magic mushroom at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of magic mushroom at Wiktionary